As many readers may be aware, Root Cause Analysis (RCA) is proposed to be incorporated into the new Global Internal Audit Standards (GIAS).

RCA is a vital tool for delivering insight and value, and it is also invaluable to develop a better thematic analysis of findings (another proposed new GIAS requirement).

As the former CAE of AstraZeneca, we used various RCA techniques, but in the dozen years I have been working on this topic with others, I have seen a range of good and not so good practices. As a result, I have just completed writing a book called «Beyond the Five Whys: Root Cause Analysis and Systems Thinking.” I was able to share a few messages at the IIA international conference in Amsterdam. However, since the session was full, I want to share some of the headline messages with other internal audit colleagues.

The first thing to say is that while the Five Whys technique is still quite commonly used by audit teams, its major shortcoming is that it implies there will be just one root cause for a problem, which is rarely the case.

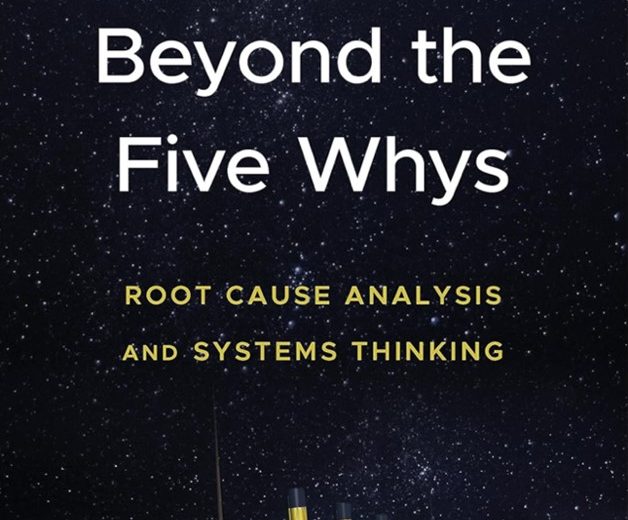

The best way of understanding why one root cause is a problem is to look at the Bowtie diagram. Here, we can see how threats and risks can result in incidents or near misses (risk exposures) which can, in turn, result in consequences of different sizes. As readers will appreciate, we use detective and preventative controls to stop incidents (or risk exposures) arising in the first place, and we use recovery controls to reduce the severity of any impact if the other techniques fail.

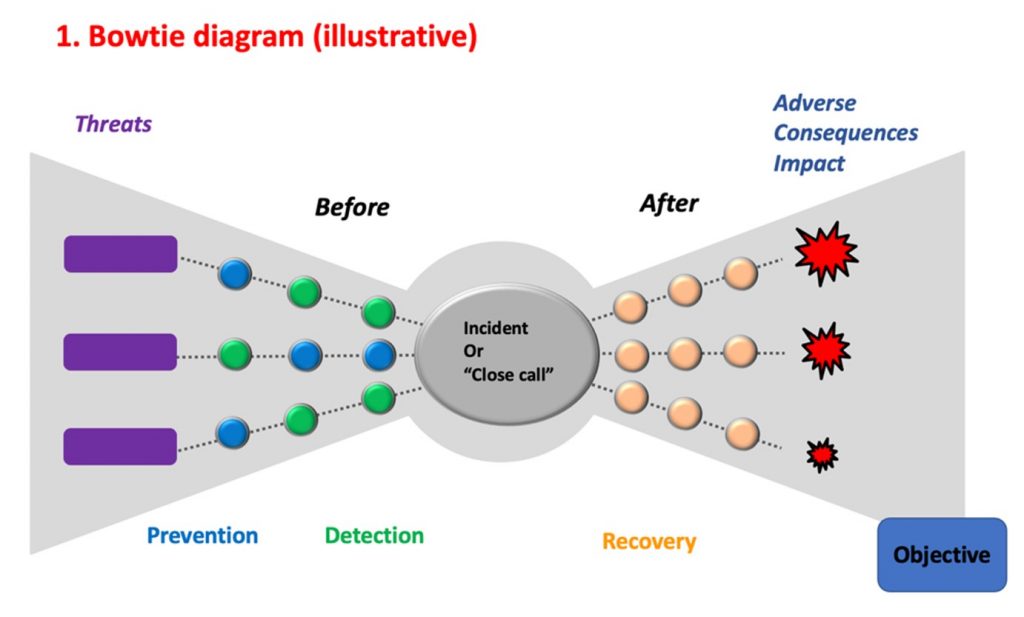

This means that if something goes wrong, or nearly goes wrong, at least one preventative and one detective control will have let us down (and possibly recovery measures as well). Basic accounting training reminds us of prevent and detect controls being needed, and the COSO framework also highlights why a range of measures are necessary to keep things ‘in control.’ This takes us to a ‘minimum viable’ RCA technique to use, which is called the Five Whys Two Legs, or the Three-way Five Whys. These are encapsulated in the diagram below.

For some audit teams it can be a challenge to ‘let go’ of having just one cause for an audit observation, but sometimes we need to take a step back to take two steps forward.

A further point that is often overlooked is to recognise the difference between different cause types. There are immediate causes, (think of a spark), then there are contributing causes (think of dry tinder on a forest floor). And then, there are root causes (i.e., the range of other things that might reduce or increase the chances of a forest fire). Root Causes are the underlying reasons why problems arise.

Understanding root causes help us address classes of problems rather than single problems or faults.

So, if a person makes a mistake, or even if they deliberately cause harm, the person will not be a root cause. After all, if we find fraud or bribery and punish the person, we still need to ask ourselves:»‘Were the anti-fraud or anti-corruption arrangements adequate?» Here, we realize, deep down, that there may have been shortcomings in risk assessments, processes, systems, etc., that explain why the fraud or corrupt act was possible, it’s not all about one person’s behavior.

As mentioned, my new book is also about systems thinking, which is about learning to step back and see the bigger picture of connections and dependencies between one thing and another. So, if we find a fraud or corrupt act we will, of course, want to punish the person who has done something inappropriate, but that should not be the end of the story. The deeper question has to be: What is it in our organization as a ‘system’, (considering its processes, policies, systems etc.), that made the fraud or corrupt act possible?

When you think this way, you start to ask questions about whether the organization is serious about addressing certain risks properly, which extends, sometimes, to questions around the clarity of roles and accountabilities, the maturity of certain processes (and the amount invested in making them work) and the way incentives and deterrents do or don’t work. In my book, I go through eight main causal factors (‘eight ways to understand why’) that can explain many problems we might see. Of course, which of the eight reasons why applies in a specific situation will depend on the particular facts and circumstances at the time.

Building on this, it’s important to be on the lookout for repeating problems.

After all, if you find repeating or similar issues (e.g., access rights not up to date, or projects running into difficulty), this is invariably a sign of systemic problems that are fuelling the repetition.

The way to understand this is to recognise that every system is set up to get the issues it currently gets, meaning we shouldn’t be surprised sometimes when we get that «Groundhog Day» feeling (i.e., «I have seen this sort of problem before!») because the underlying issues with have not been properly resolved and – until they have been – problems will keep occurring.

A few additional points are worth noting:

- Use of a fishbone technique for RCA can be helpful because it allows users to cluster the reasons for problems into common categories, which can then aid thematic analysis. Note, however, that common categories of ‘people, process and systems’ do not explain why something happened. Likewise, the suggestion that ‘culture’ or ‘tone from the top’ can be the root cause of a problem does not really explain why the culture or tone at the top is not what it should be.

- Effective RCA in internal audit starts at the beginning of assignments, not just at the end. After all, sometimes root causes for problems lie between departments or across a process. So, if you scope an assignment without thinking about possible root causes, you may find an important cause is just out of reach of what you planned to do. This then results in seeking an extension to the assignment, which can cause delays and also frustration as business colleagues are engaged at short notice on a topic they were not expecting.

- A key myth than needs to be mentioned is the idea that RCA will inevitably extend audit assignments. Indeed, as I explained in my 2015 book «Lean Auditing,» it can be a valuable tool to help you zoom in on critical causal factors during the execution of work programs and speed up assignments. This way, by the time you finish a work programme, you may already know most of the key causes.

- RCA is beneficial when writing audit reports since it can enable you to combine observations (which may be at the level of symptoms), writing key points and relevant actions at the level of the more significant (and interesting, insightful) underlying problems.

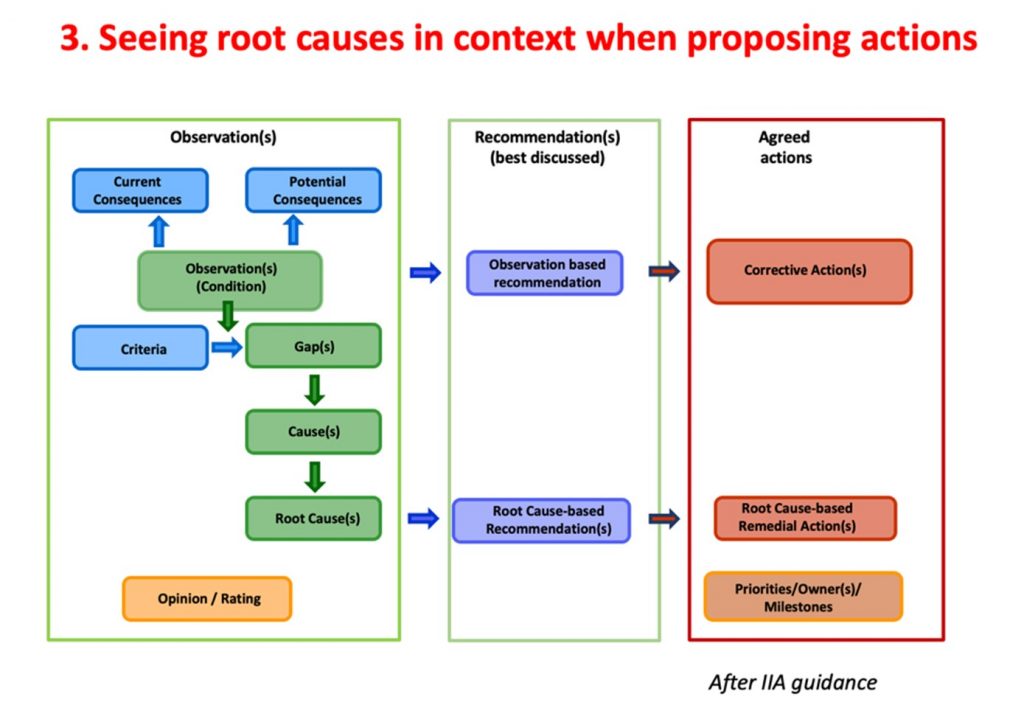

- Because, very often, actions to address root causes are more substantial, it is often crucial for the audit team to think carefully about the cost/benefit of what they propose should be remediated. In this regard, it becomes imperative to pay close attention to the potential impact of risk control shortcomings, not just the current impact of what has been found. With inspiration from the IIA guidance on report writing, we can see this point nicely spelled out in diagram 3.

Finally, being good at RCA goes beyond just what the audit team does in audit assignments. It can sometimes help an IA team think critically about current challenges. To give a couple of examples:

If we look at issues such repeated shortcomings in getting audit actions to be fully and sustainably implemented by management, or weaknesses in second-line monitoring that have been going on for several years, to what extent do these concerns also highlight areas for improvement in IA processes and procedures? Often, problems with the adequate completion of follow-up actions can stem from shortcomings in how actions are agreed, how interim milestones have or have not been set, and the clarity (or otherwise) of verification requirements to demonstrate a risk is now ‘in control.’ And concerns regarding the robustness of second line work (e.g., the quality of risk assessments or compliance documentation) can also stem from a need for more definition and clarity about the role and maturity goals of these functions (risk, compliance, but sometime IT, Finance, Procurement) and Internal Audit clearly calling this out (e.g., by using a maturity index for what these functions do).

Of course, raising these issues can be challenging for some internal audit teams, highlighting that no matter what you do on RCA, it is crucial that internal audit teams also work on their influencing and political savvy capabilities. This highlights another important message:

RCA work gives us a better understanding of some of the cultural aspects of our organizations.

So, it is worth noting that recent research by the IIA UK has identified that nearly 50 % of audit teams use RCA as a tool for understanding organizational culture. It is outside the scope of this article to explore this point in more detail, but that’s why it’s timely that the IIA is giving this important technique a new prominence.

James C. Paterson is the author of Lean Auditing and Beyond the Five Whys. Root Cause Analysis and Systems thinking, published by Wiley and available on Amazon etc.